"It seems to have been cold all the time in Blönduós, just constant cold, storms, snowfalls, blizzards and all sorts"

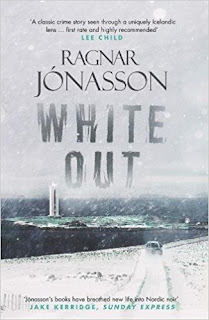

Its my turn on the White Out blogtour and I couldn't be happier! Like Jónasson's hero Ari Thór

I've fallen under the spell of the Dark Iceland series and of the remote and wild landscapes around Siglufjördur. Will White Out live up to the standard of the Icelandic crime fiction defining series so far?

Jónasson has a well honed talent for matching tense and troubled characters against a claustrophobic and often isolated setting and with White Out we're thrown right back into familiar ground. Thór is sent to investigate the apparent suicide of a young woman beneath the cliffs of a deserted village on the desperately remote North Icelandic coast; "the edge of the habitable world". The snow falls relentlessly as Thór meets the few inhabitants of this rocky out crop and soon discovers that the death mirrors that of the victim's mother and younger sister some 25 years earlier. Jónasson expertly shifts the narrative from an Agatha Christie style 'whodunit' to a well paced psychological crime thriller about family secrets and hidden social truths.

As a slice of Nordic Noir White Out delivers in spades. The use of the lighthouse at Kalfsharmarvik is a well conceived motif which, like in Jules Verne's The Lighthouse at the end of the World, adds to the drama of a crime committed in a liminial space between the sea and the land. In one interview Ari's boss Thomas questions an inhabitant, Reynir, about the 'call of the sea'. Reynir pauses before admitting "it brings a certain freedom with it".

But its not just the settings that get darker in Jónasson's novels. Ari Thór himself continues to brood throughout White Out, the 'midwinter gloom...bringing shadows into his thoughts'. This time however, we see Ari coming to terms with the idea of fatherhood. As a former theology student investigating violent crime on Europe's most Northerly edge is is hardly surprising that Thór falls for self reflective melancholy but that's to his credit, don't we want out literary protagonists to be flawed?

White Out is a great read, once again Ragnar Jónasson delivers a chilly and mysterious novel to remind us that Winter in Britain is not quite as cold and dark as we think.

I read this novel at home in cosy and warm Oxfordshire

White Out by Ragnar Jónasson translated by Quentin Bates published by Orenda Books, 276 pages.

Agree with my review? Comment and share to join the discussion #readmorebooks